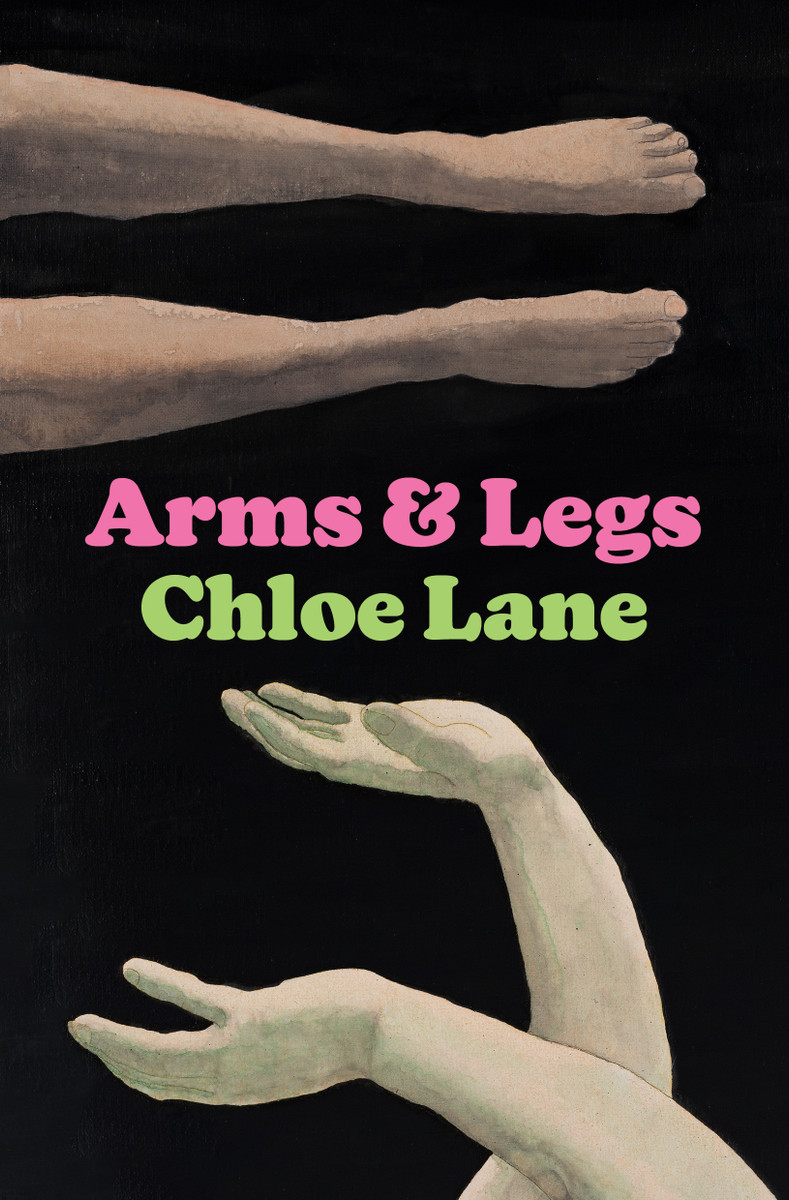

Arms & Legs, Chloe Lane’s second novel, is a careful anatomy of a marriage: the minute balances and imbalances, the connections and disconnections, the said and the unsaid.

Lane’s sparse dialogue choreographs these small arguments and even smaller reconciliations, the minor slights and the major fallouts, between the narrator Georgie and her husband Dan. He’s an architect turned furniture builder, ‘six-three and skinny, with a presence that [is] close to apologetic—the result of spending his life trying to fold himself down’. This folding down is also a shutting out, a sealing off. The novel writhes with his silent anger. It reaches its way inside the most mundane and domestic moments—as Georgie watches him separate a precut bagel, she feels as if he is doing this to her, wriggling his fingers into ‘the space between my ribs’, trying to separate them.

Georgie, born and raised in rural New Zealand, whose natural state is one of fear (fear of fires, fear of the sea, fear of the bush around her childhood home) finds herself living in Florida with Dan and their two-year-old Finn. It is a setting in which fears, both natural and unnatural, real and false, take hold. There are conversations of a serial killer who once lived in their town, and a boy from the university where she works has gone missing. Georgie and Dan’s car breaks down, and the man Gray who helps them to fix it is training his pit bull to fight. Meanwhile Finn struggles to speak; the words bubble out from his mouth in unintelligible streams.

There are snakes, bats, egrets, bald eagles, turkey vultures, diseased racoons. All around their neighbourhood, houses are vacuum-sealed and termites fumigated. They go on holiday once, and find toads have taken their place inside; the next time, the remnants of locusts. It is a landscape that makes you question what—and who—you allow in; and what slips by anyway, without your consent.

For Georgie, this is Jason, a librarian who runs Finn’s Music and Movement class—but it is also at times not Jason, not her husband, not us the reader, not anyone.

Georgie is guarded, and can be unreliable. She doesn’t always let us in on what she is about to do. A cop, working the case of the missing boy, tells us, ‘“They can be good liars when they need to be, when the stakes are high enough.”’ Georgie takes ‘they to mean everyone’; we take they to mean Georgie. When Dan thinks she is working late, she is really joining Gray for a prescribed burn in a national park. In her head is the YouTube video she watched before coming along: a man ‘looked offscreen, as if towards his captors, and said, “This place, it’s dying to burn.”’

This is, in some sense, how we must read Georgie. Her life, her husband, her son, she realises, she wanted them all. She has worked towards these things. And yet she risks them anyway. The title comes from a Barry Hannah short story about an old affair: ‘In the shadow of his regret the man described sex with the woman who wasn’t his wife as being just arms and legs, as being not worth a damn.’ This sticks with Georgie—she becomes, as she says, ‘hyper aware’ of arms and legs, their placement on a bench beside her, their exposure in the casual dress of her Florida friends, ‘[a]rms out, legs out.’ It is only near the end of the novel that she confronts this Barry Hannah quote directly again, with all her ambivalence: ‘It was only arms and legs and it wasn’t meant to be worth a damn, which was an argument for not fucking around, though it could be one for fucking around, why not?’ What is not written, but what this book still expresses, is that it is arms and legs, and it is more than that, too.

Sex, here, becomes the perfect metaphor for Lane’s prose—bare, deft, almost transparent on the page; but, at the same time, it is transcendent—the sum of her sentences say so much more than the individual words on the page. A conversation about teeth is just that, and it is also a moment in which Dan, for the first time, feels the full responsibility of parenthood, and where Georgie can relax temporarily because Dan is the fearful one. A scratch on Dan’s eye becomes an emblem of Georgie’s anger, then a symbol of how unobservant she is, how little attention she pays to Dan, then infected. Lane makes us listen to her silences; she makes them as loud as language itself.

This skill, on a line level, renders the instances that are clumsy or awkward more conspicuous than they would otherwise be. There’s the moment where she describes her own expression, almost slipping out of point of view (‘she pulled back to see my reaction, which was one of concern because she was my friend and I didn’t want to see her hurt, but also of poorly masked relief because I hated for her that her and Wren’s lives would forever be tied to that man.’) There are times where the pared back, conversational tone descends into chattiness (a dead squirrel ‘would prove to be a bad omen, though right then we had some fun with it’). There are cliches (the sight of a bird ‘chill[s]’ Georgie ‘to her ‘core’, a question ‘grip[s]’ her ‘like a hand to the throat’, she experiences a ‘rollercoaster of events’). Sometimes, the retrospective narration borders on the trite: ‘I couldn’t yet know the significance of this day’.

These moments jolt us out of what is otherwise exceptional writing. Metaphors are precise and striking. An eagle is described as ‘a high-pitched creature’; Georgie feels like the ‘casing of a snakeskin, shed and twitching in the feeble Florida breeze’; the image of a dead body ‘would clear a space in me with a sudden violence like the punch of an umbrella being opened in my chest. I didn’t want it in there–the umbrella, that feeling.’ These are metaphors that, like the dead body, like the umbrella, like the novel itself, punch you with a sudden violence. They leave you winded.

Arms & Legs, more than anything, gives you the feeling of having witnessed something authentic, something palpable. Though it is fiction, there is an emotional resonance, an emotional truth, to Lane’s words. She captures a sense of reality in an unreal place.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.