In 1912 Marie Curie – first female professor at the University of Paris, first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize, first person to be awarded two Nobels – decided to disappear for a while. She was one of the most famous women in the world; her public image was of someone selflessly devoted to science, her students, her daughters and the work of her late husband and scientific collaborator Pierre, run over on a wet Paris street in 1906.

But she also had detractors, including a right-wing press that lobbied against her election to the French Academy of Sciences – she was Jewish, they lied, and therefore not really French – and, late in 1911, broke the salacious news of Curie’s sexual relationship with physicist Paul Langevin. Langevin had been one of Pierre Curie’s PhD students; he was separated from his wife but not yet divorced.

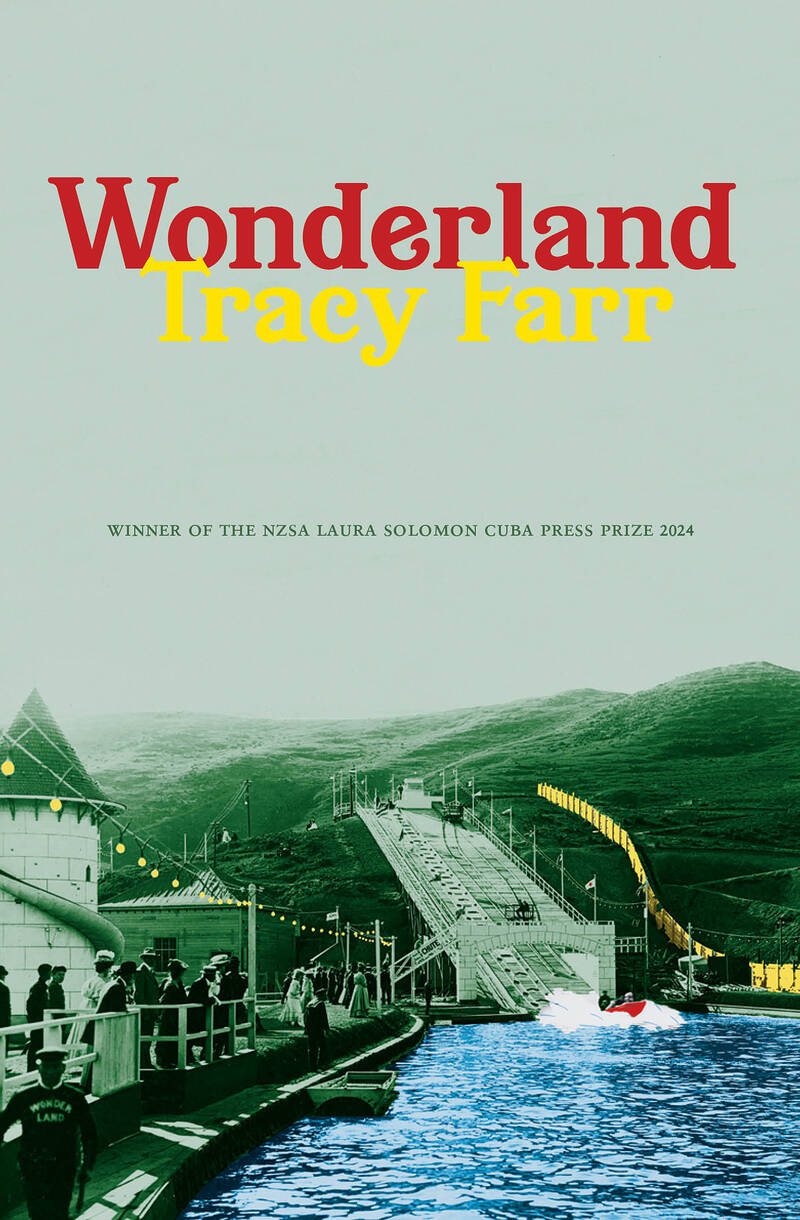

Curie was unwell, suffering from a kidney ailment that needed surgery and months of recuperation. The historical record tells us she spent most of 1912 lying low, first in France and then in England, before she was well enough to return to her lab. Wonderland, Tracy Farr’s lyrical, imaginative new novel, suggests an alternate history. Madame Curie’s friend Ernest Rutherford (‘the Great Man of Science’) suggests recovery in his distant homeland, in the home of an old school friend, Dr. Matilda (Matti) Loverock. The famous lady escapes to another hemisphere, another world. By ferry she arrives in Miramar, a quiet peninsula south of Wellington, near the road to Worser Bay. ‘In the autumn sun,’ we’re told, ‘she almost seems to glow.’

The observers here are three seven-year-old girls, Dr. Loverock’s daughters. (Oddly, they are not the only triplets in an alternate history published by a New Zealand writer this year: see Catherine Chidgey’s The Book of Guilt.) The Wonderland triplets are intelligent, musical and sensitive, ‘skinny scraps, with faces too sharp to ever be pretty’. The girls – Ada, Oona, Johanna – share point-of-view chapters, fitting for babies who grow up – ‘the space between us blurred’. Madame Curie sees them as ‘one organism, with three magnificent parts … each forever stabilising each other’.

Like the Liddell sisters, inspiration for Lewis Carroll, the triplets are entranced by a Wonderland. This one is an Edwardian amusement park, ‘Miramar’s Mecca of Merry Souls’, run by their boisterous father Carnival Charlie Loverock. He is ‘large as life and twice as marvellous’, in charge of the girls’ beach calisthenics programme every morning and training them for a star turn as the Three Miramar Maidens in Wonderland’s Winter Gala. Charlie is devoted to his family, bad at business and intolerant of ‘the whims and commands’ of Rutherford that have brought ‘Lady bloody Radium’ into their modest house.

As well as the girls, the novel splits narrative duties between ‘The Lady’ and the woman she describes as ‘mother-doctor-wife’, Matti – who graduated from medical school in Dunedin ‘in the dying years of the old century’. Matti topped her class but could only find work in ‘the womanly field of obstetrics’. She tells her daughters that their special guest is ‘a magician of chemistry’. This conflating of the worlds of wonder and science are important to the novel and to the era it depicts: this is an age of discovery and marvels. Farr, adept at point of view, reminds us of the thrill of these changes. When Matti cycles off to work at night, the

streetlights stringing the road’s edge—their new electric hum strange, still—turn her into shadow and light her shadow’s way.

Earlier in the story, after graduating from university, Matti makes her own marathon journey: she travels by ship and train to New York,

to see for herself the startling new inventions she had read about—baby incubators saving the lives of tiny earlyborns, sealing them snug as bugs in glass cases, for lifesaving medical care.

This new technology, invented by Dr Josef Dicker, is still unwelcome in conservative hospitals, so he ‘had taken a showman-like leap’ and displayed his ‘fabulous contraptions’ in carnival sideshows, the entrance fee funding the babies’ care. For two years Matti works as his assistant at the Living Infant Incubator attraction, ‘saving tiny lives under the rattle and scream of the Coney Island roller coaster’. She returns to New Zealand with three glass incubators – a ‘scientific novelty’ – and enough fittings to create ‘her own model baby hospital’ in a suitably accommodating carnival.

This is how she meets and marries Charlie, with his ‘grand dreams of Wonderland Amusement Park’. The triplets are born ‘while the paint was drying on the colourful facades and plywood hoardings’. In the first month of 1905 they become ‘Wonderland’s first residents, first act and first show’. The girls are so tiny, onlookers think of them as frail. ‘But we’re fine like tungsten filament in a blown-glass bulb, and we burn as bright’.

When Maria Sklodowska-Curie – ‘Madame Professor’ – arrives, Matti finds it hard to see in ‘this small, sad, sick woman the genius Ern promised’. Curie is a ‘woman in distress and need’ who must be nursed with morphia, chlorodyne and kindness. Matti also works long nights as an obstetrician at the hospital. She spends much of the story exhausted by work and worried about her husband’s failing business, buoyed by her ‘Cronies’, a feminist gang of friends who gather to smoke, drink and rip up offending pamphlets: they include real-life medical trailblazer Agnes Bennett (and her campaign against the misogyny of Plunket founder Truby King).

Farr is strong on sensory detail, particularly of what lies beneath – ‘every nub of hessian scrim’ beneath the wallpaper and above the timber sarking of the house; the sound when someone sits on the bed and Matti can hear ‘the horsehair in the mattress rustle and shift and slush’; the beach with its ‘cut-glass squeak of wet sand, the feather of fine tidecast seaweed’.

The girls make a doll from cuttlebone and shell that smells ‘somewhere in between socks and mothballs and the sea’. Walking in thin slippers down the house’s path of shell and stones, Madame Curie feels ‘the prick of tiny edges, little glittering sharpnesses in the night’. To her, the sand is something else to categorise and interpret: ‘Silicon, calcium carbonate, the bones and shells of tiny sea creatures, the crumblings of great cliffs, and of the Earth, and of islands’. The true wonders of the novel are, indeed, found in science and nature, in the beached whale with its ‘deep dead smell’, shaped like Halley’s comet.

Curie is associated with the colour of the ‘wondrous light’ of radium, which is ‘blue, beautiful, terrible’. The girls are entranced by her. ‘In the fabulous moonlight, the Lady’s fingertips – her blunt nails, her milk-white, blue-light skin – reflect the night’s cold glow’. She spins stories for them about a fairy-sized phial containing ‘a grain that glows like moonlight’s palest silvered blue”’ This is her ‘own wonderland’, discovered and explored with her late husband. She longs for the ‘old laboratory shed’ shared with Pierre, with its ‘rich chemical stink’ and the ‘smoke-dirtied glass’ of its windows, ‘imagining our work and lives held in memory there, lit blue, worshipped, astonishing’.

Through her eyes we see the limits of the fading Wonderland amusement park, with its shabby Japanese Kiosk selling cheese and pickle sandwiches. The highlight of the Winter Gala for Curie is not its flimsy attractions but the fireworks:

I did not expect the beautiful laboratory smell. Gunpowder, sulphur, perchlorates. Nor was I prepared for the chemistry of colours. Barium green, copper blue, sodium yellow, strontium red. This boundless laboratory is the sky above us, and all the crowd bear witness of the great experiments above. All is illumined: the empty chute that ramps to the lake, the grey-white castle façade, the man-sized plywood tower in the shape of Mr Eiffel’s. All the people in the crowd are colourless, yet brightly brilliant. They seem almost to phosphoresce, as if underwater, or to glow as if shone with ultraviolet, or the rays of light, of pure sunlight … I am mesmerised.

The novel includes a tragic turn, not hard to anticipate, but this is not a book that prioritises plot twists over characters or language. Every page is artful. Wonderland’s narrative voices are distinct and its central lie – Curie’s incognito visit to New Zealand – is utterly persuasive. The triplets tell us they ‘remember a time to come’ when Miramar will be called ‘the Hollywood of the South Pacific’ though ‘the name’ll never really catch on’, as well as a ‘time more forward still, when the seas have risen, and Miramar is an island once more’. Farr makes the fantastical seem plausible and everyday objects – a stick, a bottle, faded shreds of ribbon – conveyors of radiance and magic.

2 Comments