The 54-metre wingspan of Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North stretches across the landscape of north-east England, its body flayed, thinks New Zealand poet Kate Chaplin, at the end of her five-day reading tour with British writer Lissy Snow, ‘as if a torture had been imposed not by a human but by a god – and then the god had moved away and the angel remained’.

Back in New Zealand, Kate picks out a postcard of the angel to send to Lissy, now dying of cancer: ‘May the Angel wrap his arms around you and protect you, she wanted to write, but it was too sentimental. And if the wings did come together, it would be with a mighty clash like the arms of Tower Bridge. Easier to imagine him striding through the fields, kicking down hedges, scattering livestock and standing with one foot in a high street and the other in a pond on some village green.’

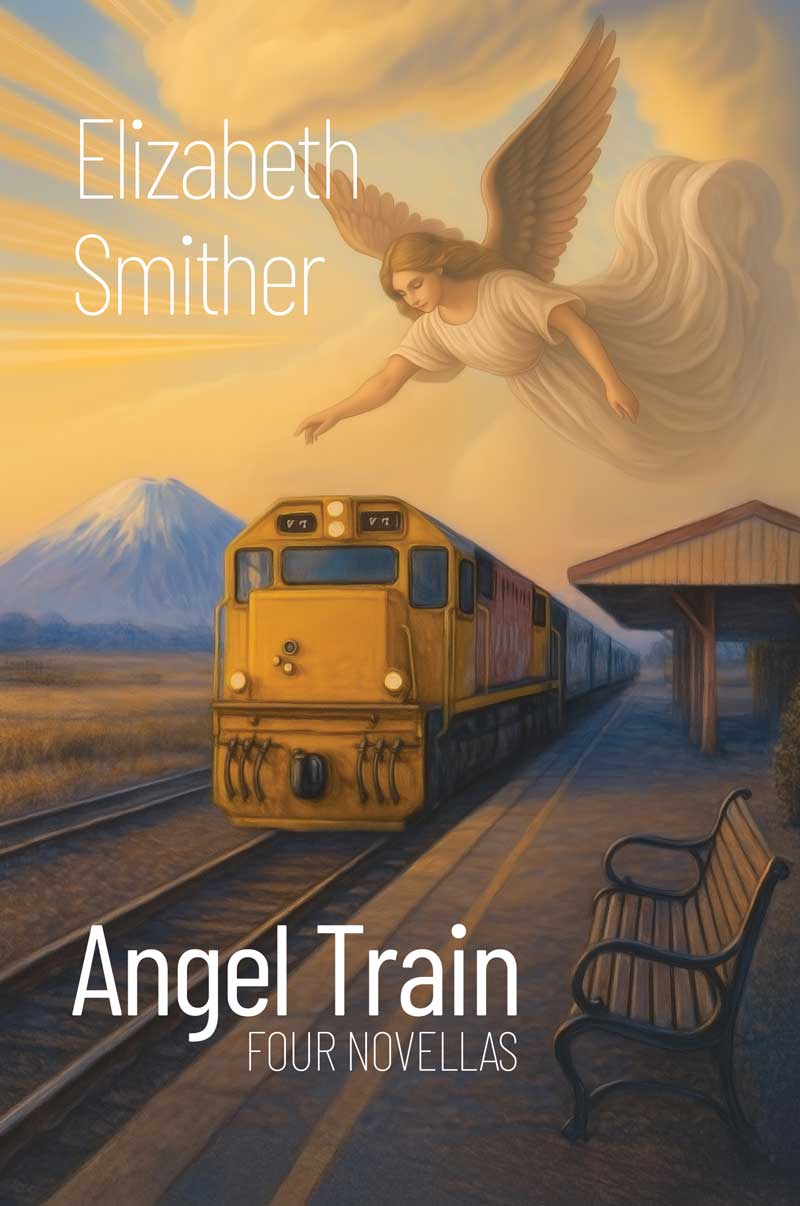

Elizabeth Smither is a poet. She is also a short story writer, a novelist and a memoirist, but it is through her poetic lens that she filters the four remarkable worlds of Angel Train.

In this first story, ‘The Glass-sided Hearse’, Smither cuts a supple path, sliding across time and perspective, shadowing her characters with a compelling if detached fluidity. More striding through fields than sentimental embrace.

She follows her characters post-reading tour. For Lissy, the daily choice of wigs (the Lauren Bacall or the Audrey Hepburn), the medical appointments, the cancer in her breast clawing and burrowing like a cat in an ‘endless snarling fight’ with the drugs. She plans her funeral, a Victorian affair with the glass-sided hearse of the title and a black plumed horse, the wonderfully named Engenouf. As she leans into the care of the palliative nurse, she imagines Engenouf ‘stamping his muffled hooves’.

Around 18,000 kilometres away – 12,000 miles, insists Smither – Kate is selecting books for housebound readers as a community librarian or giving advice to her creative writing students. Read, she wants to say. Read, and look. ‘Neither was popular. She imagined her student walking to class with headphones on, not noticing if there was a puddle on the path or raindrops falling from leaves’.

Smither notices. She notices the moonlight lighting Kate’s feet as she makes her way to bed. She notices the extravagance of an overly long Acknowledgements section in a novel. She notices the soft crying rain as the undertakers prepare for Lissy’s burial and the solidity of a friendship forged over two-bar heaters, fussy tea rooms and ever-hopeful young writers: ‘(Kate) had felt it in the air as they’d leaned together to embrace across the breakfast table, over the plates and cutlery. As if from that moment they were enclosed in a bubble that would act as a charm against whatever was to come.’

In the following three novellas, that strength of friendship runs alongside the muffled sound of relationships tearing apart. In ‘The Highwayman’, Maud Bethune oversees the general store in the historic logging town of Ouse in Tasmania. In a one-shot cinematic take, Smither pans across the gumboots, grubbers, hung rakes and kerosene lamps – Maud’s small dominion from which she offers credit, a free Sally Lunn or half an ounce of tobacco to those suffering hardship, injury or shame.

In describing Maud’s growing friendship with spinster Alice Farrar, Smither avoids excessive dialogue or explication. Rather, she tracks her characters as an unobserved bystander, as first Alice, then a cat, then a troubled niece with arsonist tendencies, move in.

Smither pivots smoothly from Maud’s unflagging generosity to that of her ancestor, highwayman Rupert Faro, living rough in the Tasmanian bush (deeper, tanglier, than Robin Hood’s Sherwood Forest) with his faithful horse Tucker. Rupert robs from the rich – apart from the bereaved – and gives to those, like Maud’s anxious customers, suffering from poverty, injury and injustice. He is a wanted man but, thanks to his chivalry and benefaction, local police encounter ‘a lode of silence, even admiration, that was hard to penetrate’.

Throughout this book, Smither threads literature, usually poetry, through her stories. In this novella, it is the driving energy and rhythmic beat of Alfred Noyes’ 1906 poem ‘The Highwayman’ (‘A highwayman come riding – Riding – riding…’). One of Rupert’s victims buys a copy of the book from a local bookseller; Rupert learns the poem as a child at school (in her author’s note, Smither concedes that Rupert was robbing coaches nearly 40 years before Noyes wrote his poem: ‘He could not possibly have learned the words of the poem at school though I fancy he may have encountered them later’).

In the third novella, Smither again has the past re-surfacing into the present. ‘Castle Nevers’ begins with the story of French countess Margaux Blanchet and her husband, Count Aristide de L’Epiny, a story handed down over two centuries. Again, the perspective slides as noiselessly as a thief. We see the Count planning his speech for his 80th birthday celebrations. He will include a special tribute to his wife: ‘Faithful, loving, doting – in their early years, to the point of stillness. Flattering to a man and then tiresome…’. But the main problem, he surmises, is what to do with the mistresses.

In another castle room, Margaux plots her escape. With the help of a former schoolfriend, a friendship ‘tested many times and never failed’, she takes flight, alighting in an attic room in High Holborn with copies of Chekhov and a jar of gillyflowers (the subtitle of this part of the story), then a sanctuary in the charmingly named village of Seahouses. This ballad-like story, embellished and romanticised over the years, is discovered by Gwyneth Porter, ‘an obscure spinster descendant who had joined a genealogical society’. She retraces the countess’ passage; she joins the Society of Romance Writers, led by the finely named Fenella Peabody (Smither seems to delight in the names of her characters, human and animal).

The story of Margaux and Aris brackets a second story. Another unfaithful husband, another wavering wife, this time stay-at-home mother-of-two Lucy Marchant. Like Margaux, Lucy realises her husband has grown to depend on her ‘in the way you count on an appliance, German or Swedish’. She recalls her younger self, preparing for her wedding: ‘Of course she would stand up for herself, she had thought … because marriage gave her power. But, surprisingly, that power had drained away.’

The final novella tilts the power balance again. ‘Kidnapped’ unfolds in Three Peaks, an alpine village in the Tongariro National Park where Josephine, Barnaby and Paula spend their holidays in a gentle rhythm of unpacking, packing, stacking firewood, drinking brandy on the station platform, afternoon tea at the Grand Chateau. Their routine is shot through with their growing intrigue around the neighbouring couple, a young man and an older red-haired woman. Lights on, lights off, a sudden noise. ’Is there a story? Paula wanted to ask. That’s what they all wanted.’

Smither leaves them wondering on the station platform to follow the story of quiet Millie Pagett: ‘Timid had been written on her school reports year after year. Confidence will come, a teacher had written in a round, right-sloping hand’. When the red-haired woman, Nyssa Graf, sets her sights on Noah, Millie’s fiancée, Millie knows she is no match.

As in the previous novellas, Millie’s victory is in her understated defiance. When she confronts her fiancée’s seducer: ‘Silence, she thought. I did not surrender silence. Let her interpret it as she pleases. I did not give her a foothold’.

These stories of friendship, flight and consolidation unfold in a masterful combination of intrigue and the observational acuity of the poet: a river, ‘moving like a muscle enclosed in silk’; ageing mistresses dressing up for their former lover, ‘necks like the bark of trees at the base of which flowers had fallen’; a dog, black-and-white face ‘divided like a playing card’ and the grand sweep of the Angel of the North, its feet bathed in the pink light of dawn, ‘as if he was warming his toes by the fire’.